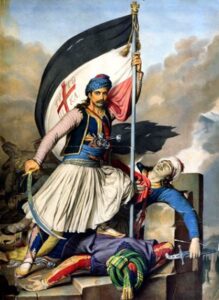

In antiquity, the term Philhellene (φιλέλλην, from φίλος/philos i.e., friend + Έλλην/Hellen i.e., Greek) was used to describe non-Greeks who were fond of Ancient Greek Culture and Greeks who patriotically upheld their culture. Philhellenism has manifested itself throughout the history of the Greek nation, including the period during and after the Greek War of Independence. Philhellenism, and the resulting aid, proved critical to the war’s success and influential in its aftermath.

Europeans since the Renaissance had studied and admired Hellenism as—in their eyes—it formed the basis of Western ideas and culture. Because of this affinity, the West was deeply moved by the Greeks’ uprising against the Ottoman Empire’s rule in 1821.

There were two types of Philhellenes: those who fought alongside the Greeks, and those who acted in favor of the Greeks from their own homelands. Up to 1,200 people came from the West, most of them Germans, to fight for the Greek cause. About 350 of them—again, mostly German—were killed or died in Greece. Many more financed the revolution or contributed to it through their artistic work.

The strongest philhellenic movement occurred in Germany (mainly in Bavaria), Switzerland, France, England, and the U.S.A. However, England’s support was the most crucial as England at that time was the most powerful country in the world.

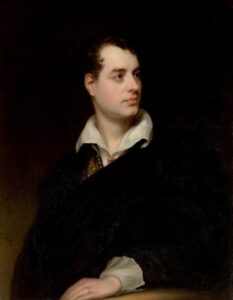

The British Foreign Secretary George Canning, who was influenced by British philhellenes, convinced the British government that it was in Britain’s interest to help the creation of a Greek state in the Eastern Mediterranean. The very English Lord Byron, a Romantic poet who succumbed to a fever right before going to war for the Greeks, was perhaps the most famous of the philhellenes. While he never had the chance to prove himself in battle, his presence helped draw the attention and arguably the material support of the then world powers to the Hellenic cause. Largely because of the efforts of these two, England provided loans, protection, and sent professional soldiers to Greece to lead the insurgents.

This support was vital, most notably in the Battle of Navarino Bay. After years of struggle, in 1827 Muhammad Ali Pasha sent a fleet led by his son Ismail to this bay on the west coast of the Peloponnese peninsula for what very likely could have been a coup de grâce. Surmising the dire situation, France, Russia, and, most critically, England sent their powerful navies to aid the Greeks and won a bloody victory. This turned the tide in favor of the Greeks, culminating in the Treaty of Constantinople in July 1832. Greece had become the first region of the Ottoman Empire to gain its independence.

It follows that Greek society during and after the war turned to England and the West rather than to Russia. Russians and Greeks had for centuries maintained a strong connection due to their common religion and enemy (the Ottomans), and Russia also aided Greece in its struggle for independence. But the West proved too powerful. They had invested both materially and philosophically in the idea of a modern Greek state harmonized with Europe; shortly after the end of the revolution, they imposed a Bavarian prince on Greece to rule as its king. This cultural, political, and economic duality—East and West—has been part of the fabric of Greece ever since.